(Note: this is a cross-post of an article I wrote for Metasploit’s blog. The original post can be found here.)

tldr: For now, don’t open .webarchive files, and check the Metasploit module, Apple Safari .webarchive File Format UXSS

Safari’s webarchive format saves all the resources in a web page - images, scripts, stylesheets - into a single file. A flaw exists in the security model behind webarchives that allows us to execute script in the context of any domain (a Universal Cross-site Scripting bug). In order to exploit this vulnerability, an attacker must somehow deliver the webarchive file to the victim and have the victim manually open it1 (e.g. through email or a forced download), after ignoring a potential “this content was downloaded from a webpage” warning message2sup>.

It is easy to reproduce this vulnerability on any Safari browser: Simply go to https://browserscan.rapid7.com/ (or any website that uses cookies), and select File -> Save As… and save the webarchive to your ~/Desktop as metasploit.webarchive. Now convert it from a binary plist to an XML document (on OSX):

plutil -convert xml1 -o ~/Desktop/xml.webarchive ~/Desktop/metasploit.webarchive

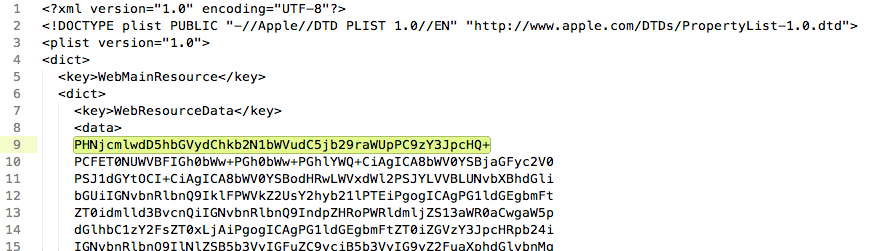

Open up ~/Desktop/xml.webarchive in your favorite text editor. Paste the following line (base64 for <script>alert(document.cookie)</script>) at the top of the first large base64 block.

PHNjcmlwdD5hbGVydChkb2N1bWVudC5jb29raWUpPC9zY3JpcHQ+

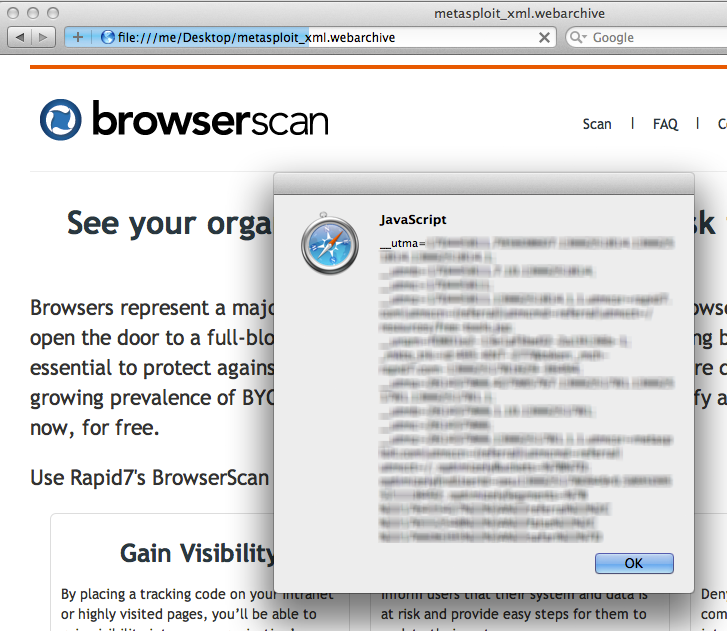

Now save the file and double click it from Finder to open in Safari:

You will see your browserscan.rapid7.com cookies in an alert box. Using this same approach, an attacker can send you crafted webarchives that, upon being opened by the user, will send cookies and saved passwords back to the attacker. By modifying the WebResourceURL key, we can write script that executes in the context of any domain, which is why this counts as a UXSS bug.

Unfortunately, Apple has labeled this a “wontfix” since the webarchives must be downloaded and manually opened by the client. This is a potentially dangerous decision, since a user expects better security around the confidential details stored in the browser, and since the webarchive format is otherwise quite useful. Also, not fixing this leaves only the browser’s file:// URL redirect protection, which has been bypassed many times in the past.

Let’s see how we can abuse this vulnerability by attempting to attack browserscan.rapid7.com:

Attack Vector #1: Steal the user’s cookies. Straightforward. In the context of https://browserscan.rapid7.com/, simply send the attacker back the document.cookie. HTTP-only cookies make this attack vector far less useful.

Attack Vector #2: Steal CSRF tokens. Force the browser to perform an AJAX fetch of https://browserscan.rapid7.com and send the response header and body back to the attacker.

Attack Vector #3: Steal local files. Since .webarchives must be run in the file:// URL scheme, we can fetch the contents of local files by placing AJAX requests to file:// URLs3. Unfortunately, the tilde (~) cannot be used in file:// URLs, so unless we know the user’s account name we will not be able to access the user’s home directory. However this is easy to work around by fetching and parsing a few known system logs4 from there, the usernames can be parsed out and the attacker can start stealing known local file paths (like /Users/username/.ssh/id_rsa) and can even “crawl” for sensitive user files by recursively parsing .DS_Store files in predictable locations (OSX only)5.

Attack Vector #4: Steal saved form passwords. Inject a javascript snippet that, when the page is loaded, dynamically creates an iframe to a page on an external domain that contains a form (probably a login form). After waiting a moment for Safari’s password autofill to kick in, the script then reads the values of all the input fields in the DOM and sends it back to the attacker6.

Attack Vector #5: Store poisoned javascript in the user’s cache. This allows for installing “viruses” like persisted keyloggers on specific sites… VERY BAD! An attacker can store javascript in the user’s cache that is run everytime the user visits https://browserscan.rapid7.com/ or any other page under browserscan.rapid7.com that references the poisoned javascript. Many popular websites cache their script assets to conserve bandwidth. In a nightmare scenario, the user could be typing emails into a “bugged” webmail, social media, or chat application for years before either 1) he clears his cache, or 2) the cached version in his browser is expired. Other useful assets to poison are CDN-hosted open-source JS libs like google’s hosted jquery, since these are used throughout millions of different domains.

Want to try for yourself? I’ve written a Metasploit module that can generate a malicious .webarchive that discretely carries out all of the above attacks on a user-specified list of URLs. It then runs a listener that prints stolen data on your msfconsole.

Unless otherwise noted, all of these vectors are applicable on all versions of Safari on OSX and Windows.

Disclosure Timeline

| Date | Description |

|---|---|

| 2013-02-22 | Initial discovery by Joe Vennix, Metasploit Products Developer |

| 2013-02-22 | Disclosure to Apple via bugreport.apple.com |

| 2013-03-01 | Re-disclosed to Apple via bugreport.apple.com |

| 2013-03-11 | Disclosure to CERT/CC |

| 2013-03-15 | Response from CERT/CC and Apple on VU#460100 |

| 2013-04-25 | Public Disclosure and Metasploit module published |

Footnotes

-

Safari only allows webarchives to be opened from file:// URLs; otherwise it will simply download the file.

-

Alternatively, if the attacker can find a bypass for Safari’s file:// URL redirection protection (Webkit prevents scripts or HTTP redirects from navigating the user to file:// URLs from a normal https?:// page), he could redirect the user to a file URL of a .webarchive that is hosted at an absolute location (this can be achieved by forcing the user to mount an anonymous FTP share (osx only), like in our Safari file-policy exploit). Such bypasses are known to exist in Safari up to 6.0.

-

Unlike Chrome, Safari allows an HTML document served under the file:// protocol to access any file available to the user on the harddrive.

-

The following paths leak contextual data like the username:

file:///var/log/install.log file:///var/log/system.log file:///var/log/secure.log -

The following paths leak locations of other files:

file:///Users/username/Documents/.DS_Store file:///Users/username/Pictures/.DS_Store file:///Users/username/Desktop/.DS_Store -

X-Frame-Options can be used to disable loading a page in an iframe, but does not necessarily prevent against UXSS attacks stealing saved passwords. You can always attempt to pop open a new window to render the login page in. If popups are blocked, Flash can be used to trivially bypass the blocker, otherwise you can coerce the user to click a link.

I am a twenty-four year-old software security engineer. In the past I've worked on

I am a twenty-four year-old software security engineer. In the past I've worked on  Github

Github